|

|

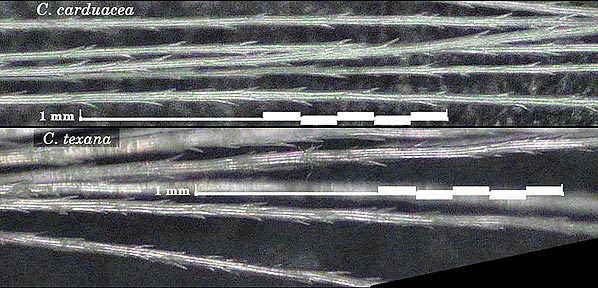

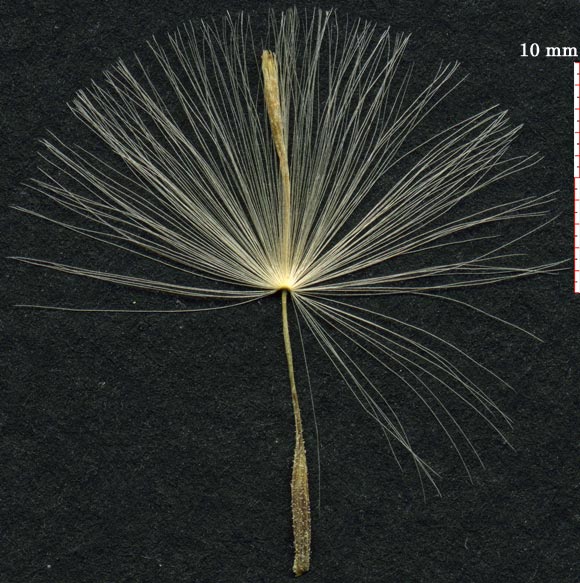

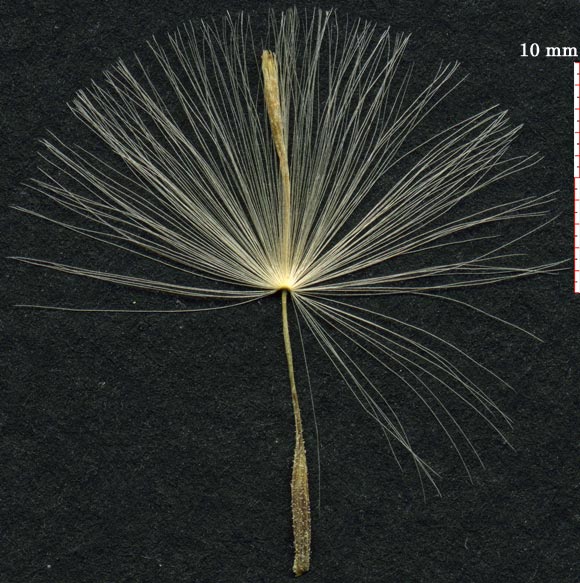

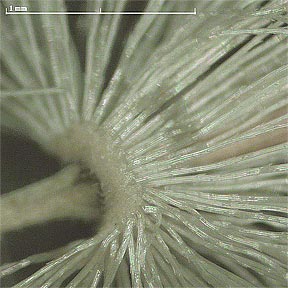

| C. carduacea (193 bristles) |

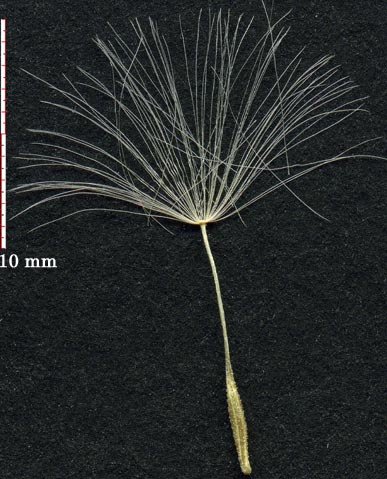

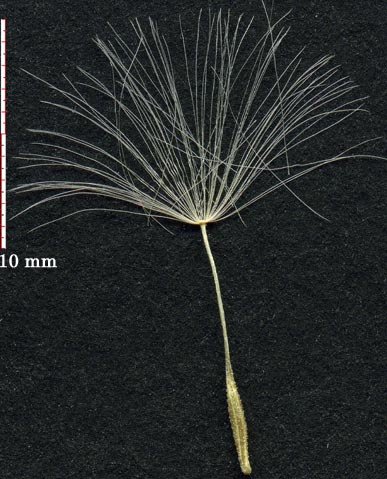

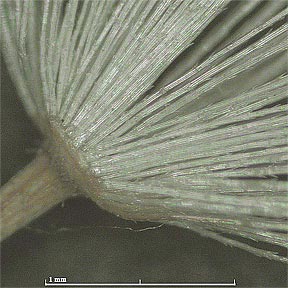

Chaptalia texana (122 bristles) |

|---|

| Click for full & larger view | |

|---|---|

|

|

| C. carduacea | Chaptalia texana |

|

|

| C. carduacea (193 bristles) |

Chaptalia texana (122 bristles) |

|---|

| Click for full & larger view | |

|---|---|

|

|

| C. carduacea | Chaptalia texana |

As is apparent from the above images, typical for these two species, C. carduacea has longer and more densely distributed bristles. The bristles of C. carduacea tend to be straight, while those of C. texana exhibit considerable curvature.

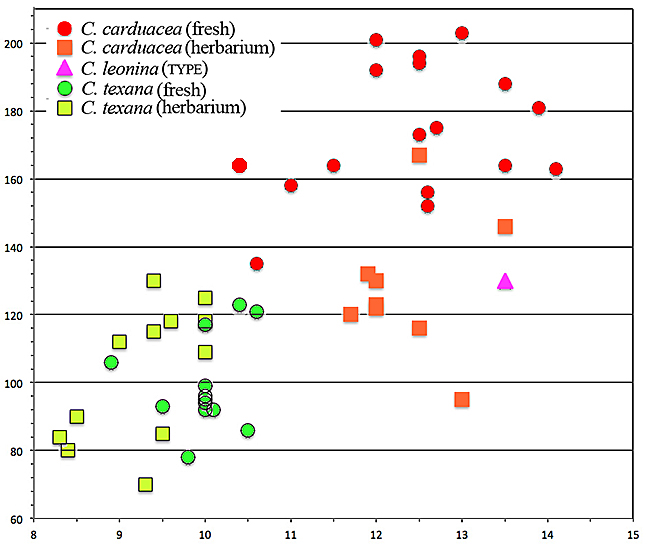

In C. carduacea the pappus bristles number 135–203 per achene (average 174) and are 10.4–14.1 mm long (average 12.0), while in C. texana the bristles number 76–124 (average 100) and are (7.6–) 8.3–10.2 mm long (–10.6)(average 9.8). The low length values in the two sets very likely reflect achene maturity, since pappus bristles lengthen up to 2 mm or more after the onset of anthesis, so that ranges in bristle length should have been correlated with length of achene beak — an indicator of maturity (as in the images at the top), but this was not systematically done until late in the study. The chart plotting bristle length × number of bristles shows that even where there is some overlap in bristle length, with fresh specimens (circles) bristle density suffices to distinguish the two species. With pressed herbarium specimens (squares), however, this is not the case. Comparing the two species, the difference in bristle counts for fresh vs. herbarium specimens is noticeably greater for C. carduacea, indicating a greater loss of bristles in pressing and handling of specimens. This tendencey for bristles to break off might possibly be related to their relative stiffness together with their greater number.

Pappus bristles are attached to a ring (annulus) at the top of the achene beak, as shown below. Here too the greater number of bristles of C. carduacea has resulted in a larger and often convex annulus. Both images are 1.5 mm wide.

| Click for larger image | |

|---|---|

|

|

| C. carduacea | Chaptalia texana |

The pappus bristles are armed with small antrorse barbs (C. carduacea 0.05–0.07 mm long & C. texana 0.06–0.1 mm long), as shown below. During early spring in the period between anthesis and dispersal the bristles tightly envelop the pistillate florets, perhaps preventing insect access to the achenes at the base of the involucre. The central perfect florets are generally not so protected, and tend to provide a tubular 'tunnel' to the achenes. I have frequently noted insect damage to these achenes, with damage to noncentral achenes only when immediately adjacent to central achenes.

Just looking at these images I am tempted to speculate that the bristles of C. carduacea are slightly more thin, which might make them more subject to breaking in pressed collections.