Irritable Stamens

by Bob Harms

|

|

|

| Normal rest position. |

Recovering from stimulation closure. |

Three stamens moved to pistil. |

B. trifoliolata stamen postures.

One well-known feature of the genus Berberis is the tactile sensitivity of its stamens (seismonasty). As insects visit the flower, seeking the nectar at the base of the filaments, contact with a filament causes it to spring toward the pistil. This is said to deposit pollen onto the insect, which in turn will carry the pollen to the stigmata of other flowers. While it is easy to trigger the stamen motion - almost any disturbance of the filament will do it - I have never personally witnessed the pollen transfer onto an insect or from an insect to a stigma. Once the insect stimulation has finished, the filaments slowly return to their normal position against the petals - this refractory period takes about 20 minutes.

The image below shows the stamens of B. trifoliolata in rest position and after tripping. Worthy of note:

- In the rest state an insect would have easy access to the nectaries at the base of the filaments;

- The petals do not move;

- The filament curvature doesn't change - changes in cell structure at the base of the filaments would seem to be the sole source of this 'bending';

- In the tripped state larger insects would be forced to withdraw across the anthers and attempts to re-access the nectaries would be blocked;

smaller insects would probably be forced to exit between the stamens and petals, upward access to the stigma being blocked.

- The stigma is slightly above the 'tooth' appendage position. This swelling/appendage at the connective base would also tend to reduce insect access to the stigma from between the stamens.

- With B. trifoliolata the pollen-bearing side of the valve appears to be angled slightly away from the stigma, reducing the likelihood of self-pollination.

A series of B. trifoliolata filament closure and eventual recovery:

The images below show rest and tripped stamens for B. swaseyi and a closed hybrid stamen that is similar to B. trifoliolata. The irritable filaments of B. swaseyi do not seem to follow the same pattern noted above for B. trifoliolata.

- The inner valve with the pollen mass has jumped to a position above the stigma, but this does not release pollen onto it - contact with an insect would appear necessary.

- My data would seem to indicate that the petals also move toward the pistil along with the stamen as the filament base bends - again contrast the hybrid image. The stamen itself does not change shape.

|

|

|

B. swaseyi — open,

valve orientation |

B. swaseyi — tripped |

hybrid — tripped |

Filament Irritability May Vary by Species

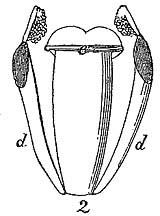

I am thus led to the conclusion that the morphology and anatomy of the irritable filament affect is not uniform from species to species, as has been assumed since Linnaeus. The various illustrations in the taxonomic literature for Berberis clearly demonstrate an enormous range of differences in stamen/filament/anther morphology. Note the representations below of Bentley's 1873 Berberis sp. stamen & pistil and Müller's 1883 stamen of B.

vulgaris:

|

|

Petal, stamens & pistil

Bentley 1873, Fig. 860, p. 412

|

Stellung der nach dem Griffel hin bewegten

Staubgefässe

Position of the stamen having moved towards the pistil

Müller 1883, Fig. 40, p.124

|

Given the functional nature of filament sensitivity – pollination by insects and also perhaps prevention of self-pollination – modifications of floral structure (both androecium and gynoecium) could well be expected to trigger adjustments in the mechanics of the sensitive response to insects.

A recent observation by Neltje Blanchan suggests that self-pollination does not generally occur with B. vulgaris, given the relative length of its stamens:

So short are the stamens, it is improbable that a flower's pollen ever reaches its own stigma except through the occasional confused fumbling of a visitor. Usually he is so startled by the sudden shower of pollen that he flies away instantly.

The tradition of the taxonomic literature is to mention filament sensitivity only as a property of the genus, sometimes with detail that is clearly not valid for our Texas species.

For example, De Candolle 1818 (pp. 4-5), provides the following description:

OBS. Stamina Berberidum plurimarum (B. vulgaris, canadensis, sinensis et verosimiliter omnium) acu secus filamentum irritata, subito supra pistillum se dejiciunt.

The stamens of most Berberis species (B. vulgaris, canadensis, sinensis and most likely all) when excited by a pin on the side of the filament

immediately throw themselves down onto the pistil.

Gray 1849 (p. 79), following

Linnaeus 1755 and other 18th Century botanists, interprets this as an act of self-pollination:

Filaments thick,...starting forward with a sudden jerk when touched with a

point next the base on the inner side (thus projecting the pollen upon the stigma)

and similarly for Bailey 1914 (v. 1, p. 487)"

The stamens are sensitive; when the filaments are touched with a pin, the fls. open, and the stamens fly forward upon the pistil.

Lebuhn and Anderson's 1994 study of B. thunbergii demonstrates that "anthers that strike an object (e.g., a glass cover slip or floral visitor) deposit some of the sticky pollen that is held together by viscin threads" (p. 257), but, as with our species, the tripping action does not dump pollen on the stigma of the same flower.

As for where and how contact must be made to trigger filament tripping, I have found that a wide range of disturbance points within the corolla, anything that could be transferred to the filament, can bring about the sensitive response. The 'pin at the filament base' will indeed work, but is not necessary.

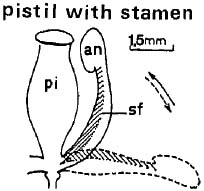

The following drawing from P. Fleurat-Lessard & B. Millet's recent article on Berberis stamen sensitivity indicates somewhat different morphology and reaction for B. canadensis than for our species:

Fleurat-Lessard & B. Millet 1984, Plate IA, p. 1334.

pi = pistil; an = anther; sf = stamen filament; hatch = adaxial half

Apparent differences are:

- The filament is straight in rest position and then bends toward the pistil in response to a stimulus. The authors state: "Stamen filaments of Berberis flowers ... respond to various stimuli (mechanical, electrical, chemical, etc.) by bending" (p. 1332). If the parenchyma cells responsible for the bending in B. canadensis do occur along the full height of the filament (the hatched area), then the overall bending affect should be expected.

- The stamen and stigma are at the same height, the position of the open valve is not given (perhaps not considered relevant for their anatomical study?).