Species Diversity

Native species originated, evolved, and adapted to natural ecosystems in a given geographic area. The geographic scale can be a continent, a hemisphere, or an ecoregion. Approximately 20,000 bee species have been described worldwide, about 4,000 species inhabit North America, and nearly 1,000 live in Texas. In Travis County, straddling Edwards Plateau and Blackland Prairie Ecoregions, 336 native bee species have been described and 236 were found in the Brackenridge Field Lab of the University of Texas at Austin. It has ~60 acres of woodlands and prairies along the Lady Bird Lake portion of the Colorado River. Bee scientists (melittologists) must collect bees to identify them, and often find the most prevalent species, the Western honeybee, Apis mellifera, among their collecting pans and sweep-nets.

Introduced Species

Apis mellifera was introduced to the Americas in the 1600’s by European colonizers who brought honeybees in cone-shaped apiaries for honey, wax, and mead. Honeybee colonies propagated on family farms and ranches across the continent. About 4,000 honeybees are kept in average U.S. apiaries, but commercial apiaries truck millions of bees cross country to commercial farms for pollination services. Tens of thousands of honeybees forage on crops, weeds, and native plants around farms. Those large colonies have large foraging capacity that overwhelms local floral resources, sometimes to the exclusion of local native bees.

Europeans were not the first to market honey in the American continent. Some honeybee species are native to Neotropical forests. In southern Mexico, people have harvested honey from stingless bees since pre-colonial times, when honey and wax was traded between Mayan and Aztec empires.

Pollination Services or Gifts?

Pollination is an essential ecosystem function. Butterflies, moths, beetles, wasps, flies and bees help plants reproduce by transporting pollen among flowers. Unlike bees, other insects are incidental pollinators, while native bees actively pollinate 87% of flowering plants in the wild. ~30% of fruit, vegetable, and nut crops rely on pollination to set fruit. Every third morsel can be traced to insect pollinator activity.

Laura Russo shows a drab breakfast without bee pollination…

and a colorful, balanced breakfast, thanks to bees! Do you notice the difference?

Bees share the fruits of their labor! Download a Pollination Services poster.

Native Bees Love Native Plants

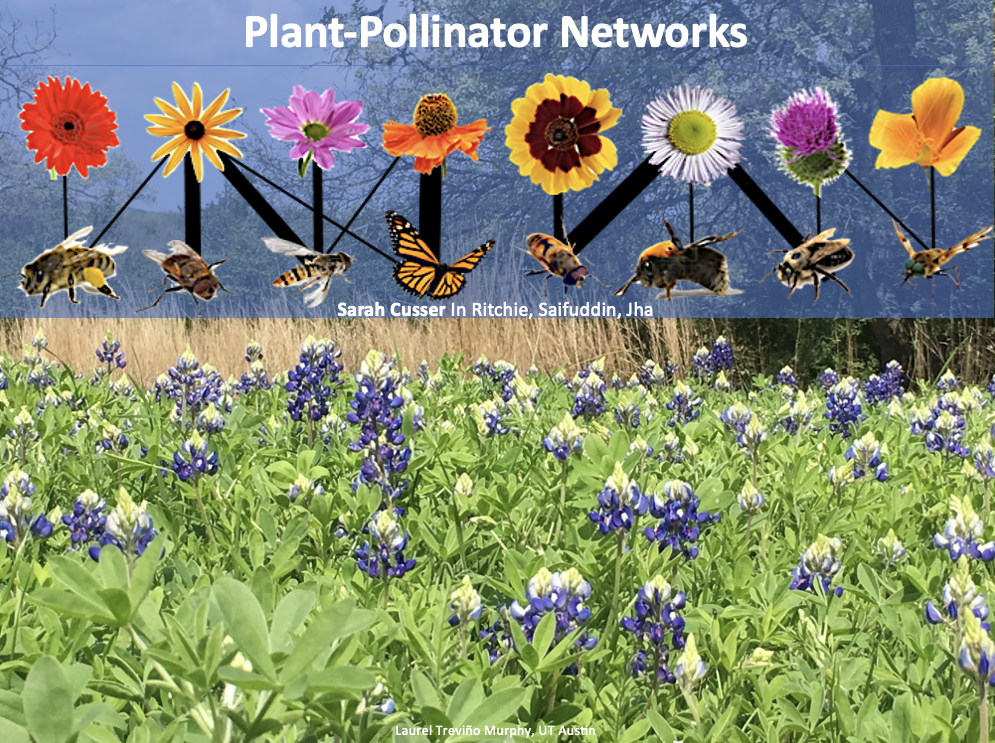

Native bees are part of insect communities in ecosystems where ecologists study Plant-Pollinator Networks. Most flower-visiting insects are incidental pollinators who visit flowers for nectar. Female bees actively collect pollen, which is essential for their larvae to develop. Native bees prefer foraging on native plants in landscapes around farms.

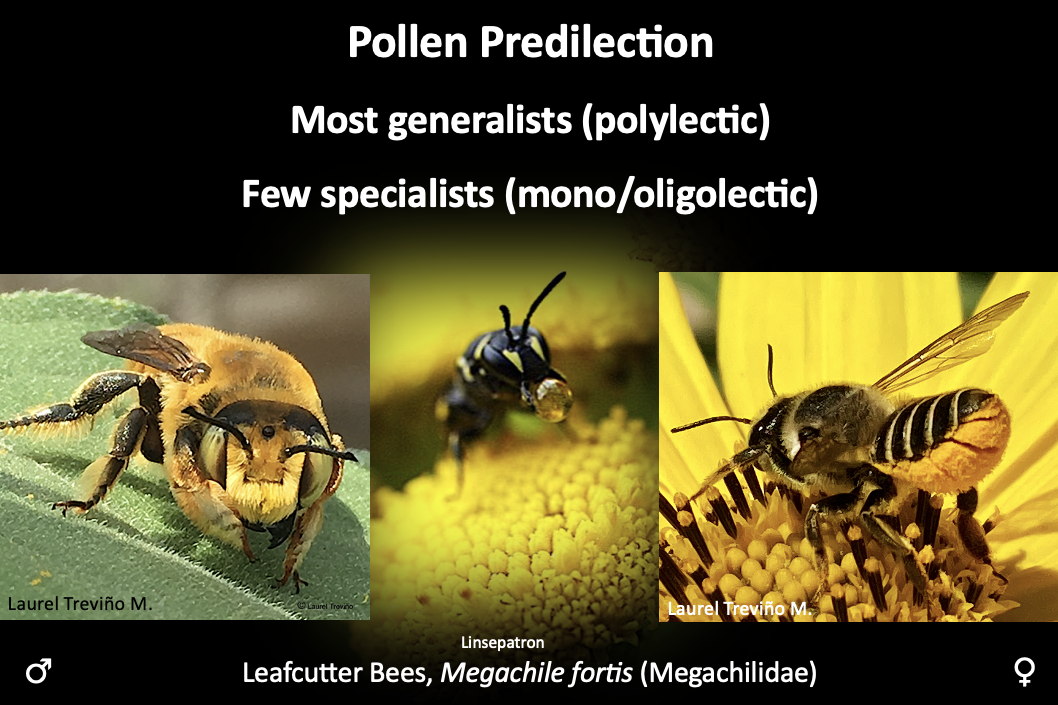

Most native bee species are generalists who collect pollen from various plant families. Fewer species are specialists who obtain pollen from one plant genus. If their preferred flowers aren’t present, some oligolectic specialists will just forage on other species. Generalist bumble bees love sages & asters. Squash bees forage on squash.

Foraging Ranges

Bees are centric foragers who conserve energy by nesting near their food, Bed & Breakfast style. Flight distances relate to species and size. Large bees can forage between 100~600 yards (500 meters to 1 kilometer). European honeybees forage between 1~3 miles around apiaries. Tiny tropical bees can gather pollen from 1.25 miles (~2 km) away! Bees may fly farther in search of good plentiful floral resources.

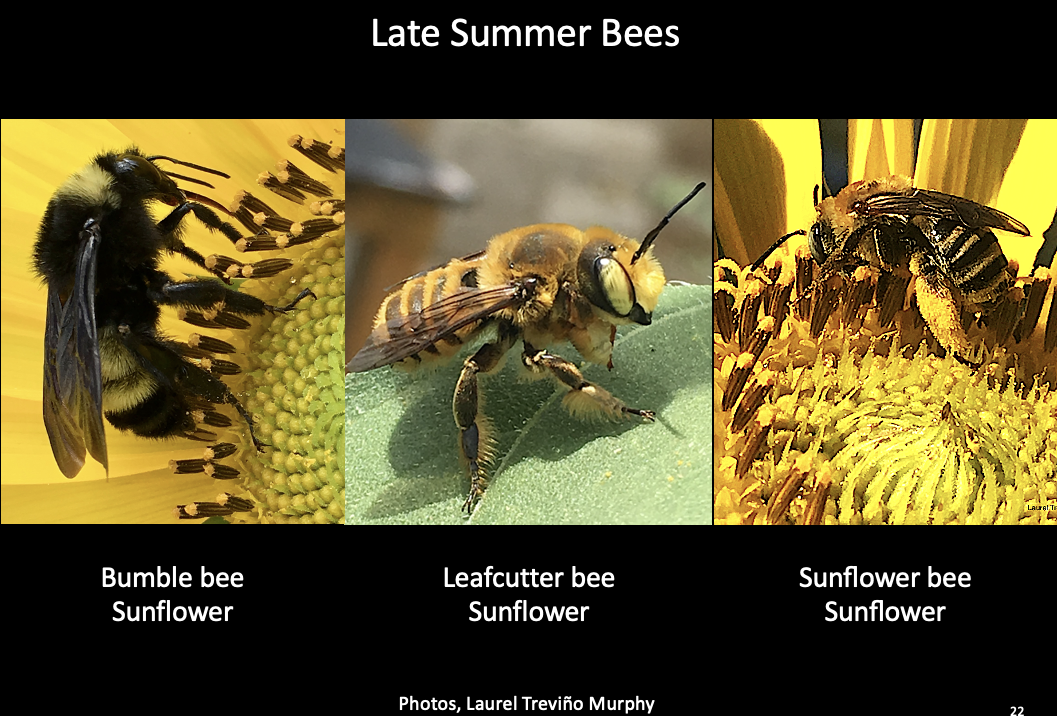

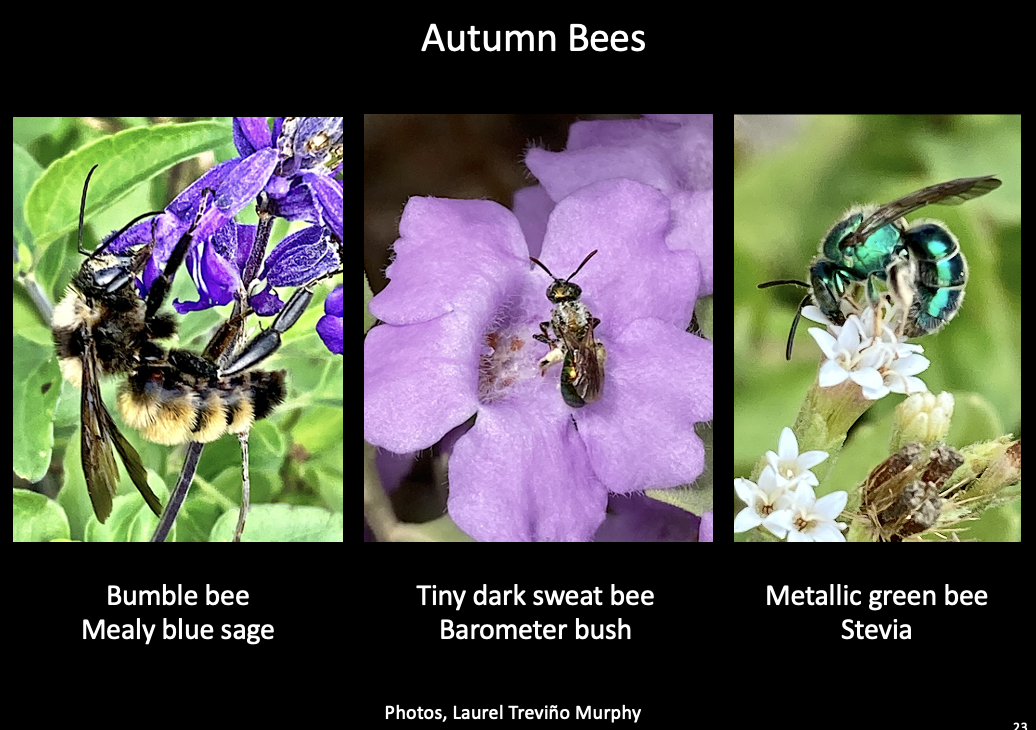

Foraging Seasons

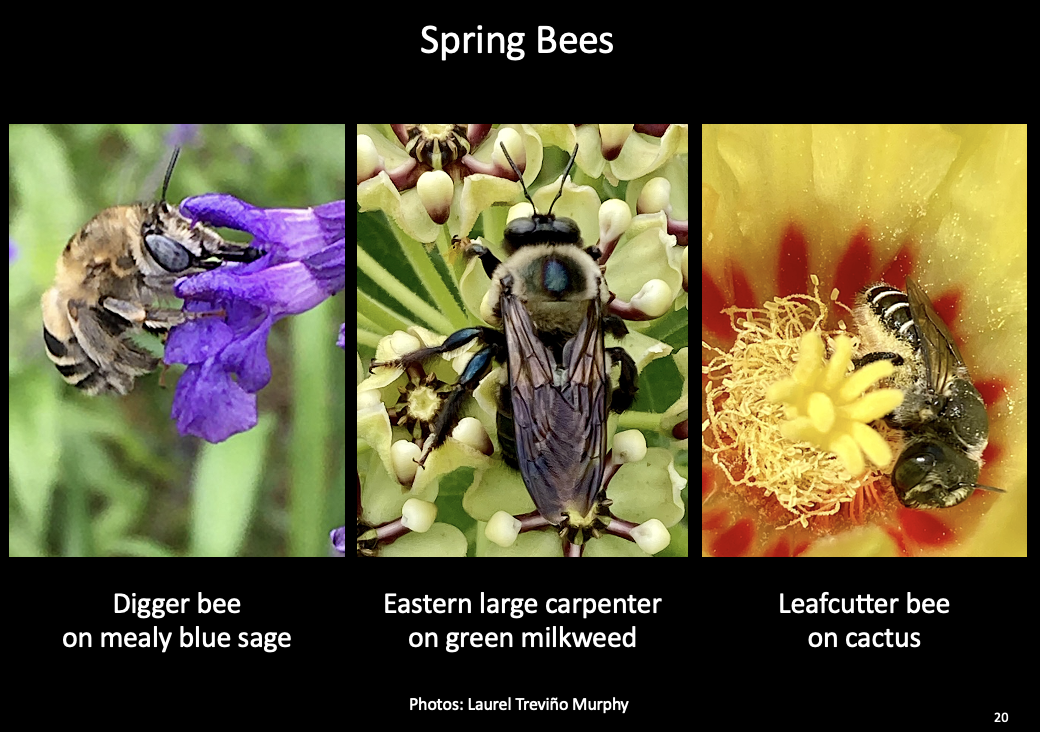

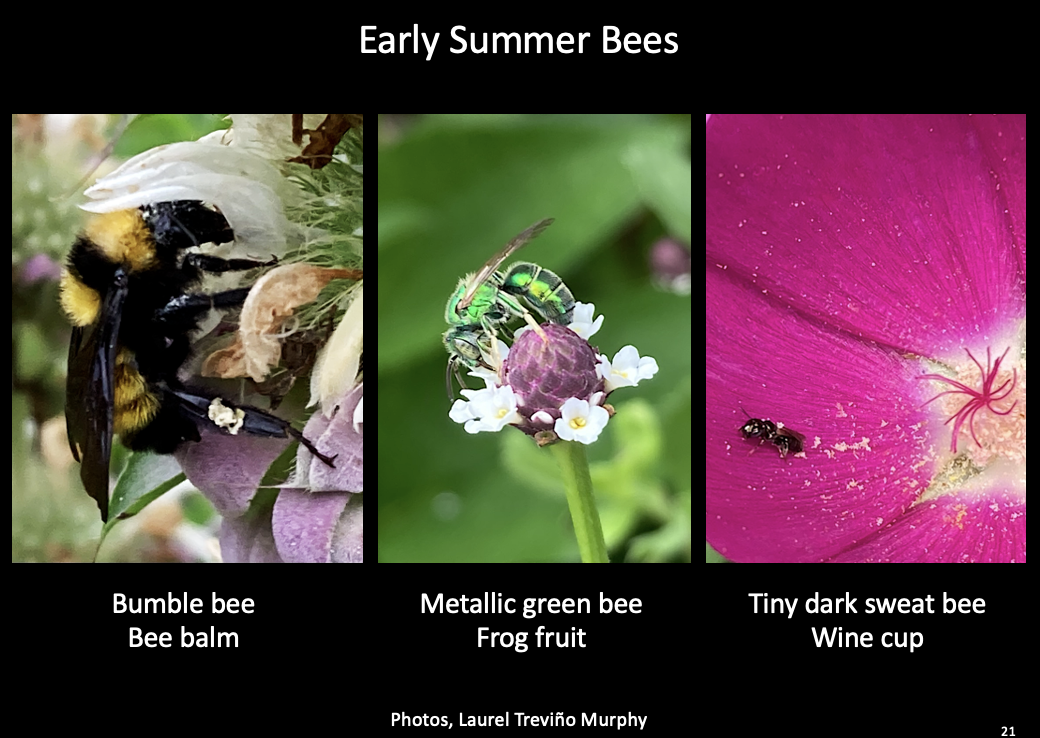

Pollinating insect life cycles progress with seasons across landscapes. Adult bees emerge from nests when plants are flowering. Native bee foraging seasons coincide with native plant bloom seasons. Various bee species forage in successive sequence as spring progresses to summer and autumn. Unfortunately, climate change disrupts their seasonal blooming-foraging synchrony.

Foraging Time

Most bees forage by day but crepuscular bees forage at dusk or dawn. Bees discern shades of gray with three, tiny, simple eyes (ocelli) atop their head, and see colors with large compound eyes. They see in the UV light spectrum, so a yellow flower may look blue! Bees smell with antennae.

Halictus poeyi, by Sam Droege, USGS, Native Bee Inventory Monitoring Lab

Marvelous Mutualisms

Flowers attract pollinating insects with colors or aromas, and reward them with nectar or pollen. Bees find colorful flowers readily and their agility allows them to manipulate flowers to reach their rewards. Large bees open sage or legume flowers by lowering the keel petal. In some bee species, females vibrate their flight muscles vigorously–sonicating to the tune of C–to shake pollen from fused anthers. This is how bumble bees buzz-pollinate tomato, potato, and chile flowers (Solanaceae), mining bees buzz-pollinate blueberry or cranberry flowers (Ericaceae), and green sweat bees sonicate other native species. Other bee species, such as Apis honeybees, don’t sonicate flower anthers.

Bees are methodical foragers, consistently visiting the same species each trip. This floral fidelity makes bees excellent cross-pollinators. Bees have branched hair–fuzzy split ends–that pick up spiky pollen. Some bees collect dry pollen with hair combs on their underbelly or hind legs; others stuff moist pollen in hair baskets on their hind legs. Most bees are scopate, fewer are corbiculate.

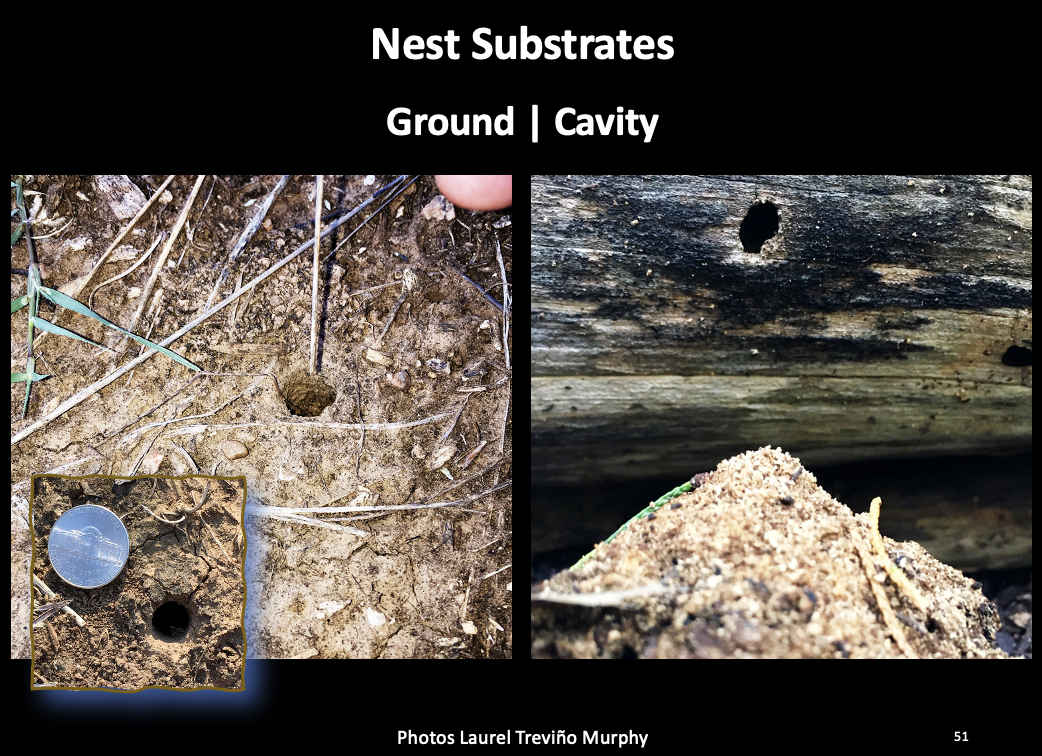

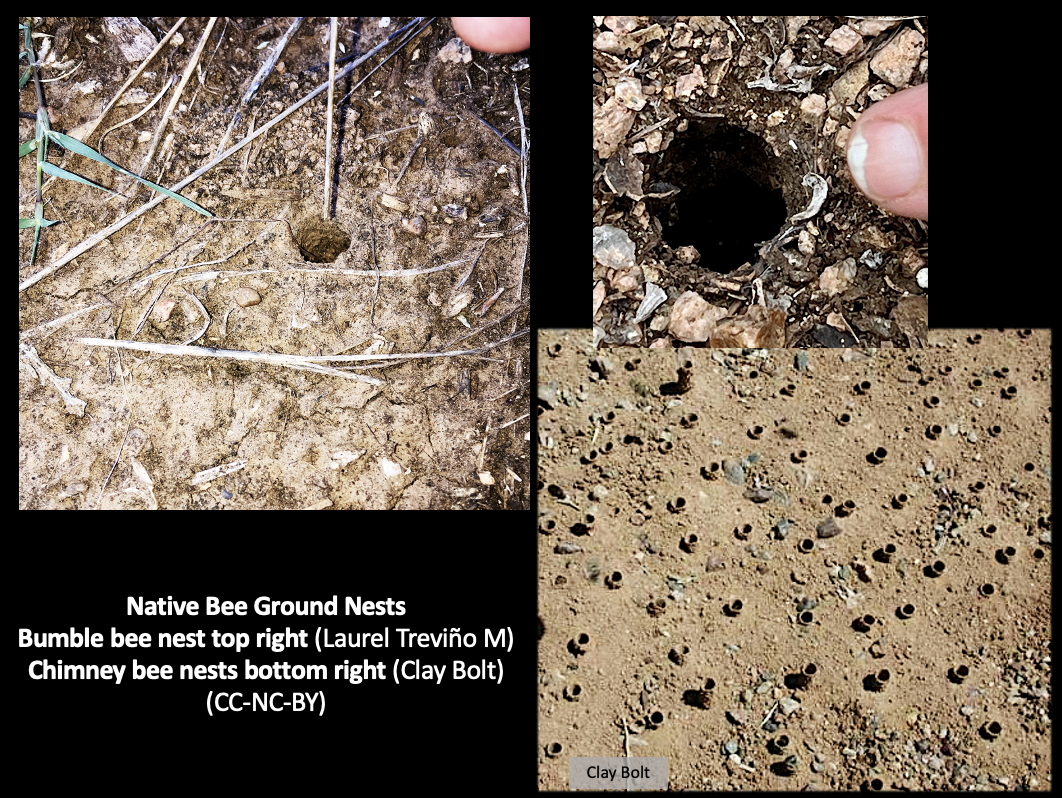

Nest Substrates and Resources

Bee species consistently nest in a given substrate, above or below ground, using local resources to make nests. Females choose sites near nest-building resources. Some chew leaves or mud mastic, others use resins or wax to partition each chamber where they lay a single egg on a pollen loaf or liquid food, then plug the nest entrance with the same material. In North America, about 70% of native bees are ground-nesters while 30% are cavity-nesters, in forests, shrub-lands or prairies (Poster).

Ground Nesting bee species dig 6-in to 2-ft tunnels. Digger bees make level entrances to deep underground nests. Chimney bees build turrets. Bumble bees nest under grass thatch or in mouse holes. Cellophane bees smooth walls with the underbelly and apply secretions with the tongue for waterproof linings. Abrupt digger bees nest in slopes or banks (Austin Nature & Science Center caliche bank).

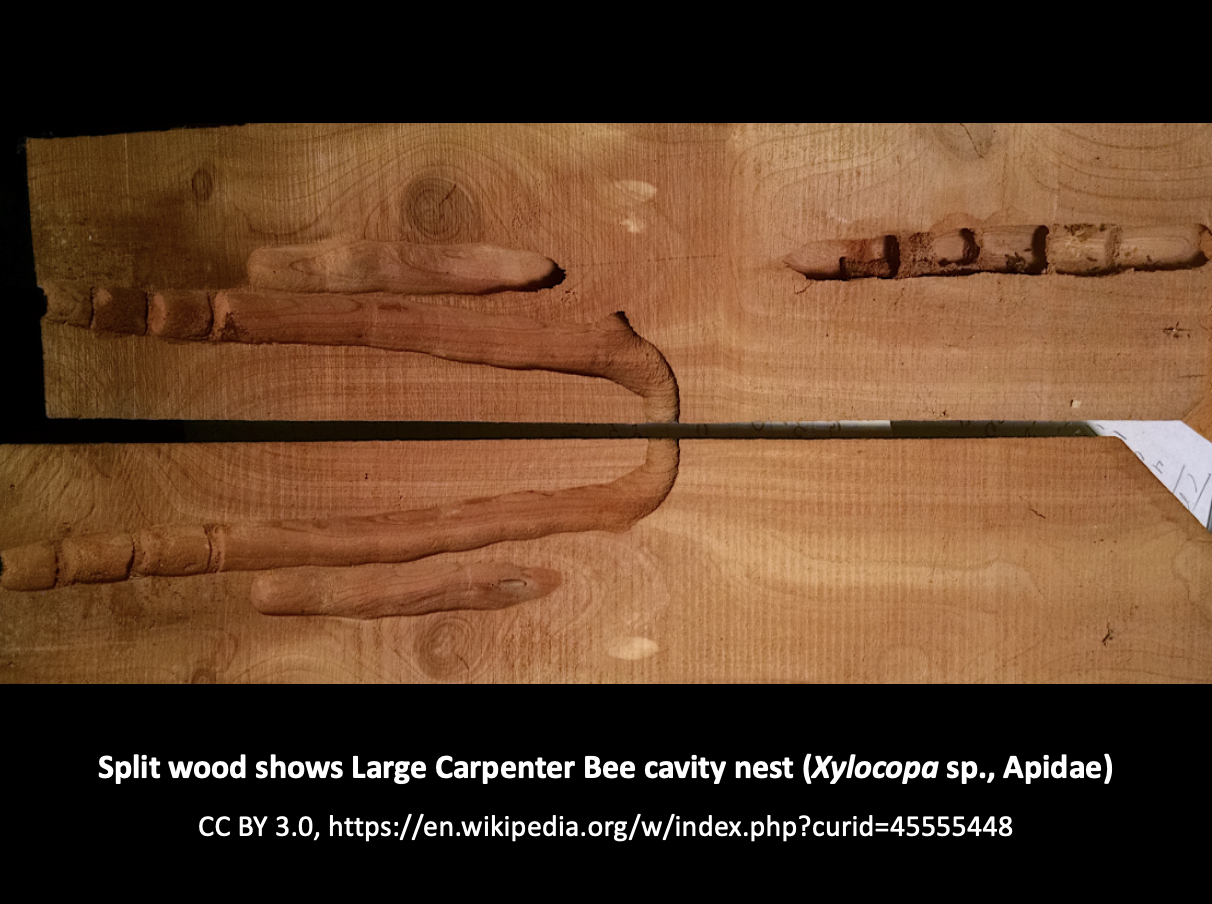

Cavity Nesting bee species like Leaf-cutter bees line and partition cavities with pieces of leaves and flowers. Mason bees retrofit bamboo reeds or rock crevices with mud mastic for plugs (photo Scott Famous). Small Carpenter Bees carve into pithy stems, like other twig-nesters, and make ‘particle-board’ partitions with pith mastic (photo Alain C.). Large Carpenter Bees carve long nests in soft old wood.

Native Bee Sociality

Nesting habits are tied to bee species sociality. In northern North America, 90% of native bee species are solitary nesters, where a single female, makes her nests and amasses provisions for each chamber (mass provisioning). Gregarious solitary bees can aggregate many nests in good nesting substrate, but each mother stocks her own nest. Some species are communal nesters, where females share a common entrance but provision their own separate nests. Sweat bees and cellophane bees are communal nesters who continually provision their nests (progressive-provisioning). Primitively-social bumble bees form small annual colonies, where daughters of the same age (cohort) progressively provision their younger sisters. Social bees form large permanent colonies where females continually provision hundreds of wax cavities with developing larvae. Examples of social bees are the four species of Apis honey-bees, and stingless (Meliponini, Apidae) honey-bees that Mayan people have cultivated since pre-colonial times from southern Mexico to Central America. Social bees are an exception in the bee world.

Sociality – Nesting – Diet

Sociality, nesting, and diet traits help describe how each bee species functions in an ecosystem. Each species has an ‘ecological curriculum vitae‘. The ‘Bee-Bio‘ for most North American native bee species can be expressed in a three-word phrase: solitary, ground-nesting, generalists. Solitary native bees lay relatively few eggs, and larval development depends entirely on the provisions their mom can gather in her short lifetime. Foraging adult bee populations shift seasonally in sync with floral resource availability. Diverse floral abundance, and nest substrates and resources are crucial for native bees. That is why forage and nest resources are limiting factors for bee populations and dispersal.

Native bees’ lives are as ephemeral as bloom seasons!

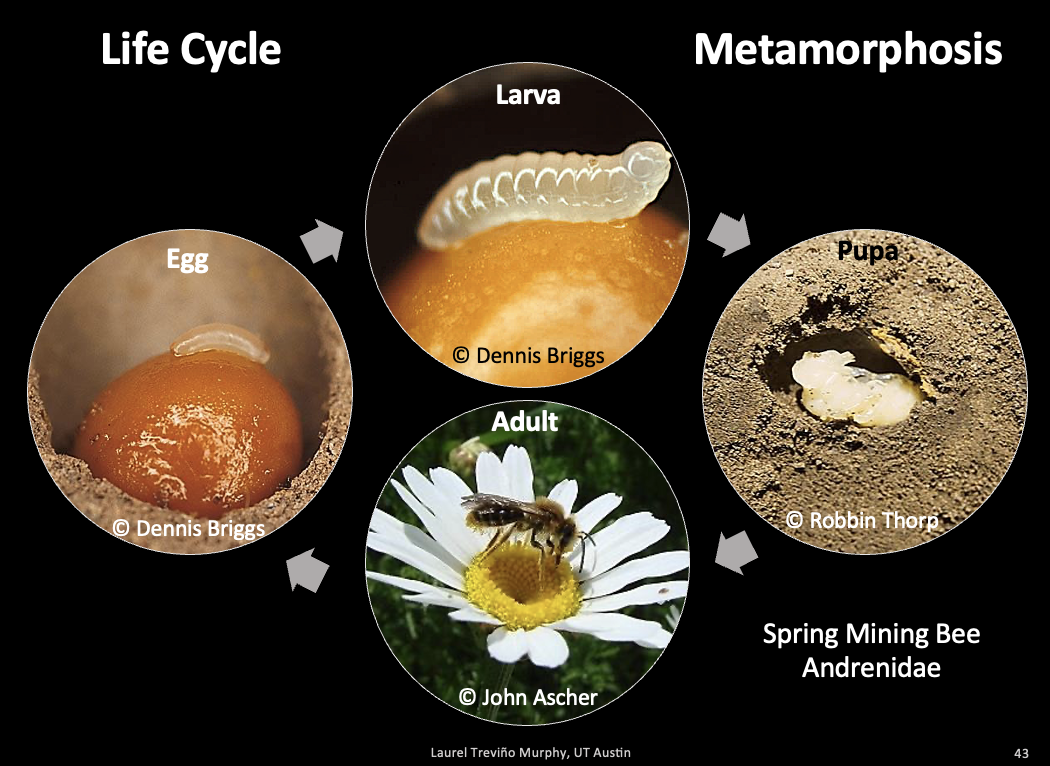

Bee life cycles have complete metamorphosis with four developmental stages: egg, larva, pupa, adult. Females lay eggs on pollen loaves or near liquid food in each incubation chamber. Eggs hatch and develop into larvae who consume all the provisions their mom left in precise amounts before plugging the chamber. After changing form (metamorphosis), the pupa can remain in its chamber for many weeks and emerge from the nest when conditions are right. Native bees spend most of their life in a nest. Adult mason and mining bees can live a month, bumble bee queens live a year but their offspring live four weeks, and large carpenter bees lives longer. Large bees have longer life spans than small bees, who live two or three weeks … a Texas Hill Country bloom season.

Bee, Wasp or Fly?

- Bees are herbivores who only consume pollen, nectar or plant oils

- Wasps are carnivores who eat insects and often drink nectar

- Flies are detrivores who eat plant/animal decay or drink blood/nectar

- Bees & wasps: 4 wings, long elbowed antenna. Flies: 2 wings, stubby antenna

- Bees & flies: round bodies. Wasps: narrow body, svelt waist, pointy abdomen

- Bees have plumose (feather-branched) hair that carries pollen loads

Alas! Meet Our Six Bee Families

- Apidae Robust hairy Bumble bee & Large carpenter bee, hairless Small carpenter bee

- Megachilidae Leaf-cutters & Masons line/partition nest with leaf/mud mastic

- Halictidae Sweat bees are mostly small & dark or green with metallic sheen

- Andrenidae Fuzzy Mining bees dig deep ground tunnels

- Colletidae Striped Plasterers partition/plaster nest with mastic or secretions

- Melittidae Fluffy Plant-oil collecting bees live in arid climates

See common native bees in Central Texas gardens and Bee ID Guide webpage!

Native bee habitat includes many pollinating insects. Native bees need floral and nest resources. Logs, snags, pithy stalks/stems, and grass thatch, help cavity-nesters. Natural vegetation that retains soil and non-compacted ground, helps ground-nesters. Native bees prefer native plants. In subtropical Texas, newborn bees forage on milkweeds, mealy blue sage, and American basket flower in spring, adult bees forage on sunflowers and aster species in hot summers, and females forage on autumn sage and Maximillian sunflower to provision winter nests. Healthy bee communities live among diverse and abundant floral resources including wildflowers, bunch-grasses, shrubs, and trees that bloom in sequence. Small populations of native bees forage spring through fall, while large populations of Apis honeybees forage year-round. Beekeepers can also help native bees by augmenting native plants in landscapes. Good beekeepers are good neighbors.

Download poster: Pollinator Habitat Conservation (en español).

Page content was developed by Laurel Treviño Murphy (Jha Lab Outreach Program Coordinator) and Margarita López Uribe (Pennsylvania State University Assoc. Prof.). Laurel linked more resources (PDFs) for you to download for education or conservation purposes. Photos are BY Laurel Treviño Murphy (LTM), unless otherwise attributed. Please do NOT copy photos since copyrights apply to some. Contact: ltrevino@austin.utexas.edu

Photographers’ permission granted to Jha Lab for educational purposes.

(CC-NC) Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike, © Copyright protected